Why Aren’t You Trying To Save Pandas? Rethinking the Faces of Conservation

Why conservation needs more than just cute mascots to make a real impact

I was knee-deep in a project trying to protect river ecosystems teeming with overlooked, uncharismatic species — tiny fish, aquatic insects, swampy plants most people wouldn’t glance at. But this question caught me off guard: Why aren’t you working to save Pandas?

I didn’t know how to answer at first. Not because I didn’t care about pandas, but because the question itself revealed how narrow our conservation spotlight can be.

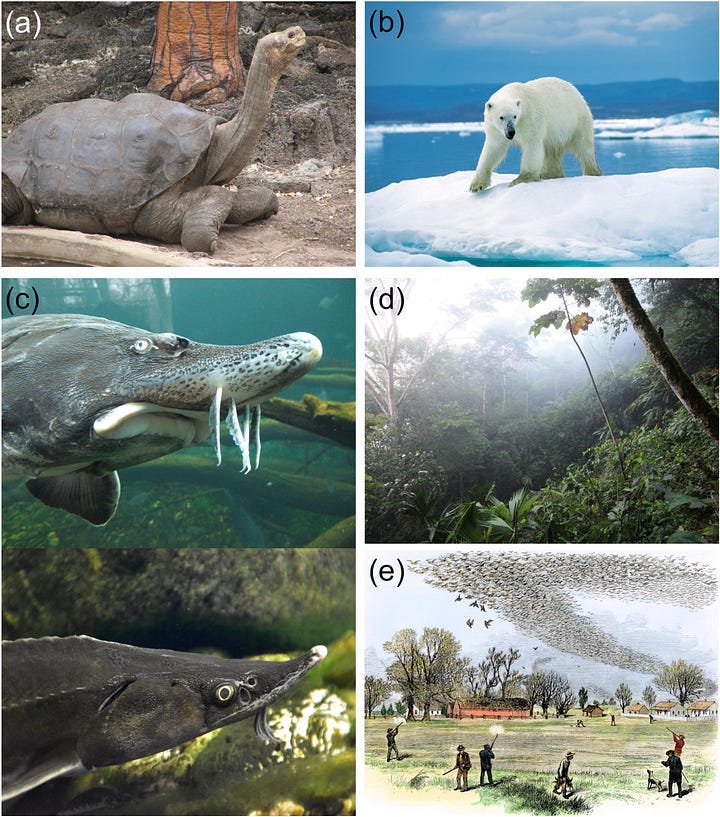

We tend to put animals like pandas, tigers, and polar bears on a pedestal. They’re cute, they’re famous, and they’ve got the kind of charisma that melts hearts… and opens wallets. But what about the last living individual of a tortoise species, or a fleeting natural event like a mayfly emergence that turns a river into a cloud of shimmering wings?

These are powerful symbols, too. They just haven’t been marketed that way.

A new study published in Biological Conservation makes a case for exactly this kind of shift. Led by Dr. Ivan Jarić and a team of international researchers, the paper introduces the concept of the “flagship entity” — a broad, flexible way to think about what can represent and rally support for conservation.

Rather than sticking to a few charismatic megafauna (big animals), this framework invites us to expand our imagination and strategic toolbox.

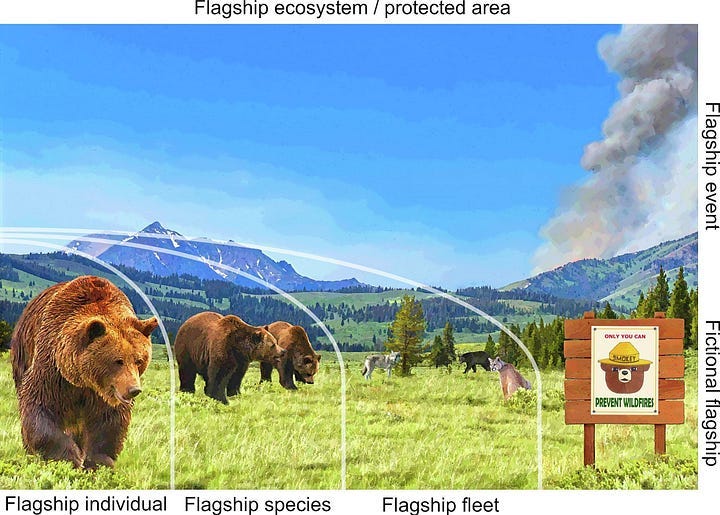

“While a flagship entity certainly can be an animal,” Jarić says, “it can also be a forest, a coral reef, a ‘celebrity’ individual such as ‘Lonesome George’ the tortoise, or even a spectacular natural event.”

The study builds a unifying theory that organizes these entities — species, individuals, fleets, ecosystems, even events — into categories, and then provides a roadmap for how to choose and use them. The goal? To make conservation more emotionally resonant, culturally relevant, and, ultimately, more effective.

To ground their proposal, the authors draw examples from across the world. Think of Grizzly 399, a bear so famous in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem that she drove tourism and awareness until she died on October 22, 2024, at age 28.

Or the six species of Danube sturgeon, used together as a “flagship fleet” to represent a whole river’s worth of conservation needs. They even include fictional flagships like Smokey Bear, a cartoon that helped shape fire awareness for generations. These examples aren’t just catchy; they show how diverse the faces of conservation can be

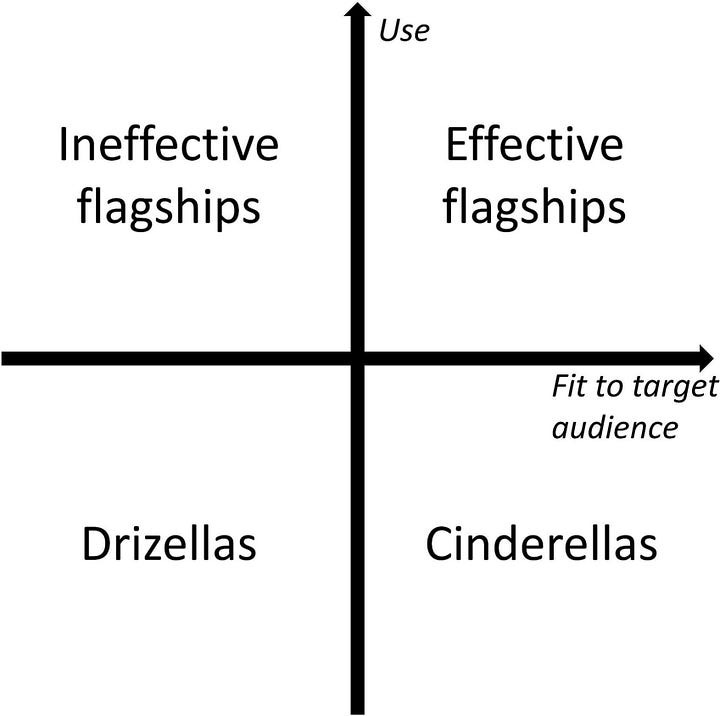

To construct their framework, the researchers reviewed the scientific and marketing literature, synthesized case studies, and proposed a simple but powerful classification tool. Flagship entities, they suggest, should be evaluated on two main axes: how well they resonate with a specific audience, and how much they are currently being used.

Some, like pandas, are both popular and widely used. Others, nicknamed “Cinderellas,” have strong potential but remain under the radar. Then there are the “Drizellas,” whose traits (think: scary, slimy, or misunderstood) may work against them despite their ecological importance.

But charisma, they argue, isn’t everything.

“It is important to bear in mind that the most effective conservation flagships aren’t always the biggest, most colorful or famous animals,” says co-author Dr. Diogo Veríssimo. “What matters more is how well they resonate with specific audiences.”

That means conservationists need to stop assuming what people care about and start listening instead. The paper recommends applying marketing principles like audience segmentation and message testing, much like political campaigns or public health initiatives do.

The authors even suggest borrowing models from behavioral science, such as the COM-B framework, to understand how awareness leads to actual change.

This feels especially relevant to those of us who’ve worked in the field. I’ve seen how quickly a campaign can flop when it misses the emotional mark, or how a local plant that no one’s ever heard of can become a community symbol once its story is told the right way. People respond to connection, not obligation.

The paper also urges us to measure impact more seriously. Too often, we assume that putting a cute animal on a poster will translate into conservation wins. But how do we know if it changed minds, or motivated policy, or actually raised enough funds to protect habitat?

The authors point to tools like culturomics, the analysis of digital data like Google searches and social media trends, to track public interest and tweak campaigns accordingly.

At the same time, the study acknowledges real risks. Turning a species into a celebrity can lead to unintended consequences: black markets, over-tourism, or distorted messages that simplify complex ecological realities. And using landscapes as flagships can, if done carelessly, erase the people who’ve long lived in and cared for those places.

That’s why this new framework isn’t just about expanding what counts as a flagship; it’s about being more intentional. More thoughtful. And yes, a little more creative.

Dr. Sarah Crowley, another author, puts it well:

“With biodiversity loss threatening ecosystems around the world, it is crucial to rethink how we inspire public support.”

If we want conservation to succeed, we need to stop relying on the same faces and start telling richer, more diverse stories. Not every symbol needs to be a panda. Sometimes, it’s a forgotten river, a vanishing tradition, or a single tortoise named George.

Those stories matter too.

Thank you for supporting independent science writing! Your support helps keep these stories free for everyone, spreading science, trust, and action. I couldn’t do this without you!

If you enjoy my work and want to help me keep these stories free for everyone, I’d appreciate your support at any level that’s comfortable for you:

💡 $1/month or $10/year – A small boost with a big impact.

🌱 $2/month or $20/year – Supporting science communication.

🔬 $3/month or $30/year – Investing in evidence-based insights.

🌍 $4/month or $40/year – Expanding science for everyone.

🚀 $5/month or $50/year – Powering independent science writing.

Every contribution helps me continue creating content that makes science accessible, engaging, and impactful.

With Love,

Silvia P-M, PhD

Climate Ages

Unfortunately people are fundamentally selfish and expect there to always be something “in it for them” when it comes to conservation. People like saving pandas because then they can go see them at the zoo and post their pictures online. Other considerations are pretty secondary.

Nature is not for pleasure, it is to teach you what peace is and that you cannot by nature be neutral or submissive or blind. If you truly feel the existence and meaning of nature, you must create a basis for peace by changing yourself and the people, to change the banking and capitalist system into a unified social system, an ideal for all: justice, value, fair distribution of wealth, equal sharing of opportunities, etc. Life is to realize the ideal, to know it, to be for it, to live for it, to sacrifice everything for it.