What Happens to a Forest When the Birds Are Gone?

New research reveals how missing seed dispersers are quietly limiting tropical forest recovery

When I left academia to work in conservation, I landed in an organization fighting for the Amazon. I thought I understood the stakes: biodiversity loss, deforestation, vanishing cultures. But it wasn’t until I started looking at forest regrowth patterns that I realized how incomplete my understanding really was.

I knew birds and monkeys helped disperse seeds, but I didn’t grasp how much forest recovery actually depends on them, not just in theory, but in real, measurable, limiting ways.

A new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) just added a huge piece to that puzzle.

Led by Dr. Evan Fricke and colleagues, the paper asks a deceptively simple question: What happens to tropical forests when the animals that spread seeds are missing?

Spoiler: recovery slows down… a lot.

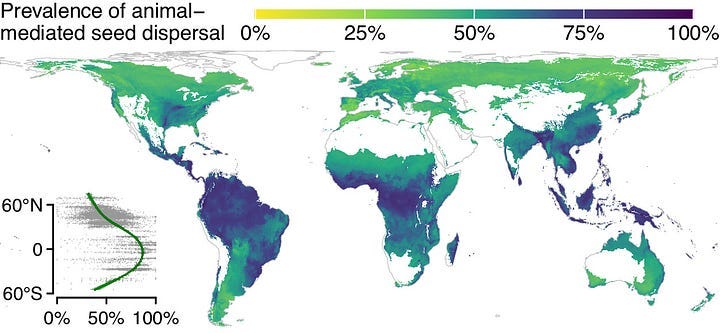

The research focuses on a problem we rarely talk about outside of ecological circles: seed-dispersal limitation. Many tropical trees rely on fruit-eating animals to carry their seeds far and wide.

Think of a toucan eating a fruit, flying 500 meters, and pooping the seed out where sunlight hits the ground just right. Now take that toucan away. Suddenly, that seed might fall straight to the forest floor, beneath its parent, where it has to fight for light, nutrients, and space.

And in a regrowing forest, one that’s trying to come back after being cleared, that difference can make or break the future of a tree species.

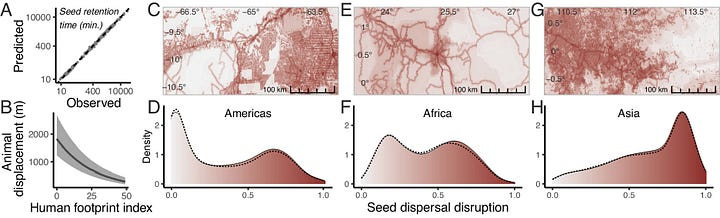

Dr. Fricke’s team combined global maps of over 3,000 tropical tree species with models that simulate how far seeds can go with or without large seed-dispersing animals. Then, they compared these maps with areas of secondary forest: places where agriculture has been abandoned and nature is trying to recover.

The results were shocking.

In more than 60% of these recovering forests, key tree species no longer have access to seed dispersers that can reach them. Not because the landscape is unsuitable, but because the messengers are gone.

To put it bluntly: we’ve silenced the forest’s delivery service.

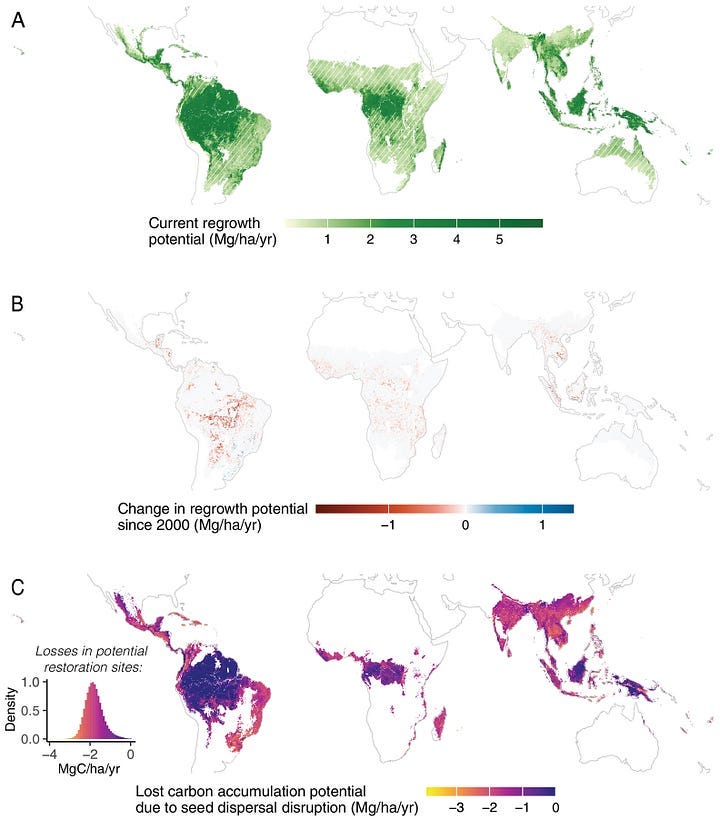

This breakdown has serious consequences. Forests in the tropics are one of the world’s best carbon sinks. They pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, host incredible biodiversity, and support the water cycles that millions of people depend on. But if the right tree seeds never make it to the right places, forests don’t just grow back slower; they grow back differently.

The authors explain it this way: “Seed-dispersal limitation is geographically widespread, limiting tree species’ contributions to forest regeneration across 95% of tropical secondary forest.” In other words, the very trees that could help restore forest structure and function can’t get their seedlings to where they’re most needed.

What makes this finding especially urgent is that it’s not just a future problem. It’s already happening. The seed dispersers, especially large birds and mammals, have been disappearing from forests for decades due to hunting, habitat loss, and fragmentation. Some forests still look lush from above, but they’ve been emptied of the animals that keep them functional.

This study doesn’t just point out a problem; it offers a direction. If we care about restoring tropical forests, protecting frugivores must be part of the strategy. That might mean thinking beyond replanting efforts and looking toward rewilding, improving connectivity between forest patches, or reducing hunting pressure on key species.

These aren’t fringe ideas. They’re central if we want forests that don’t just regrow, but recover with resilience.

During my time in conservation nonprofits, we often focused on land: acres saved, fires prevented, new seedlings planted. But this paper reminds me that land alone isn’t enough. You need the movement. You need the connections. You need the quiet flutter of wings carrying life across space.

It’s easy to think of forests as self-healing, but they’re more like networks. Disrupt the network too much, and even if the pieces are still there, they won’t function.

The most eye-opening part of this work is that it’s global. It’s not about one forest or one species. It’s about a process that underpins recovery across entire continents. And it’s happening out of sight: no bulldozers or chainsaws involved, just the slow absence of flights that used to happen every day.

For those of us working on nature-based climate solutions, this is a wake-up call. Regrowth isn’t automatic. Restoration needs allies. And some of those allies are feathered and furry, swinging from branch to branch or gliding between trees.

Losing them doesn’t just silence the forest’s voice: it cuts off its future.

Thank you for supporting independent science writing! Your support helps keep these stories free for everyone, spreading science, trust, and action. I couldn’t do this without you!

If you enjoy my work and want to help me keep these stories free for everyone, I’d appreciate your support at any level that’s comfortable for you:

💡 $1/month or $10/year – A small boost with a big impact.

🌱 $2/month or $20/year – Supporting science communication.

🔬 $3/month or $30/year – Investing in evidence-based insights.

🌍 $4/month or $40/year – Expanding science for everyone.

🚀 $5/month or $50/year – Powering independent science writing.

Every contribution helps me continue creating content that makes science accessible, engaging, and impactful.

With Love,

Silvia P-M, PhD — Climate Ages

P.S.: Want to build a visible, fundable, and purpose-driven science brand?

Join the Outreach Lab waitlist and be the first to know when doors open this September.

I know of a recent line of mathematical research has considered integral equation-based models specifically geared towards measuring these types of phenomena; these are often called nonlocal models and have been shown to be superior to partial differential equation models with regards to accurately representing these very types of ecological dynamics!

Silvia. Hi. I live off grid on 300 acres of wet sclerophyll forest in the Byron Bay hinterland, east coast of Australia. I was born in Australia in the mid 1940's. Years ago, our skies were darkened in the late evenings by thousands of bats... flying foxes, those wonderful fruit eaters that dispersed rainforest seeds over hundreds of kilometres. Not any more. Their populations are in serious decline due to massive government promotion of urbanisation and farming. Climate change with large bushfire & heatwaves are adding to the catastrophic decline. In 2018, 23,000 flying foxes perished due to heat & fires. Government policies still allow, shooting & netting of these wonderful flying mammals. I am lost in the insanity of converting beautiful Australian coastal forests into horrible suburbia all in the name of progressive & economic growth. Humans are a disaster to this planet. People will never see a tree or a forest bat as more important than a new suburb or new shopping mall. The real madness is that the gifts of a crashing environment & climate change will be passed on to their grandchildren. Your article about birds being a vital need for forest growth (and of course we have major bird populations in Australian forests), reminded me about the crashing populations of fruit bats. Thank you. And in the end, Entropy Always Wins.