How Ancient Climates Are Warning Us About the Future of Rainfall

A major Atlantic current is weakening, and with it, the rains that keep our planet breathing

When I first started working with paleoclimate records, I never imagined just how relevant they’d become for understanding the future. At the time, I was more fascinated by what they could tell us about the past: how mammal communities responded to past climate changes, how prehistoric ecosystems collapsed or bounced back, and what that all meant for evolution.

But over the years, something shifted. We began noticing that the data I’d gathered to make sense of ancient climates was increasingly helping answer a more urgent question: what comes next?

This isn’t just a scientific hunch anymore. A new study warns that some of the rainiest places on Earth (the Amazon, Central America, and West Africa) could face severe droughts in the not-so-distant future. The culprit? A slowdown in one of Earth’s major ocean circulation systems: the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC.

If you’ve never heard of the AMOC, you’re not alone. Most people don’t think about ocean currents when they think about tropical rainforests. But as I’ve learned through years of connecting ecological dots, everything is linked.

The AMOC is one of those hidden engines of the climate system, moving warm, salty water from the tropics to the North Atlantic and helping regulate global temperatures. More importantly, it helps keep the tropical rain belt, a band of heavy precipitation near the equator, in its usual spot.

But climate change is disrupting that rhythm. As ice sheets melt and rainfall increases, the ocean’s surface water becomes less salty and less dense. That means it can’t sink as easily in the North Atlantic, which slows down the entire circulation. Even a small reduction in the AMOC’s strength could throw off precipitation patterns around the globe.

And this isn’t just theory, it’s starting to show up in observations.

Back in 2005, DiNezio was a technician at a NOAA lab in Miami, calibrating some of the earliest measurements of this massive current system. At the time, he didn’t expect it would become the focus of his scientific career. But the data spoke clearly.

In the years that followed, scientists started seeing signs of a slowdown. While the AMOC later appeared to rebound, the fluctuations raised concern. With just two decades of direct measurements available, it’s hard to know whether we’re witnessing a temporary blip or a long-term trend. What’s clear is that models consistently predict a weakening if warming continues.

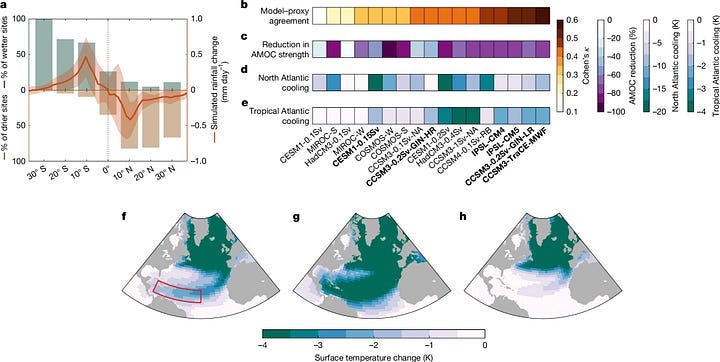

That uncertainty, combined with the potential consequences, is what drove the study forward. Instead of relying solely on modern observations, the team looked backward. They turned to the end of the last Ice Age, around 17,000 years ago, when the AMOC last slowed dramatically due to natural changes.

Clues from cave formations, lake sediments, and ocean mud told the story of how rainfall patterns shifted across the tropics. These paleoclimate archives are the kind of evidence I’ve worked with myself, and I know how powerful they can be. They carry the fingerprints of long-lost climates, offering a glimpse into how Earth responds to change.

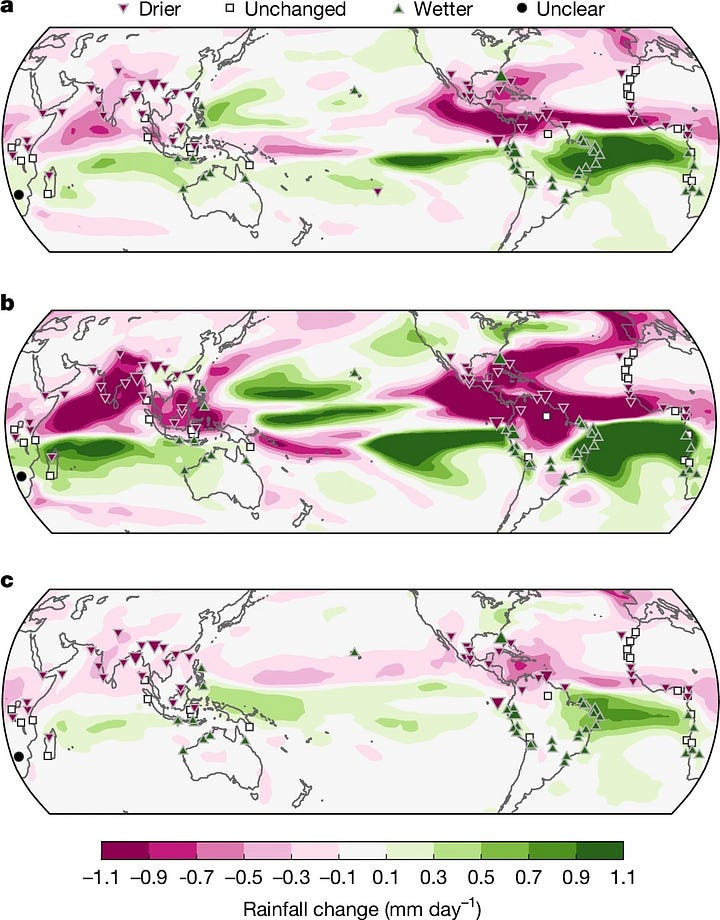

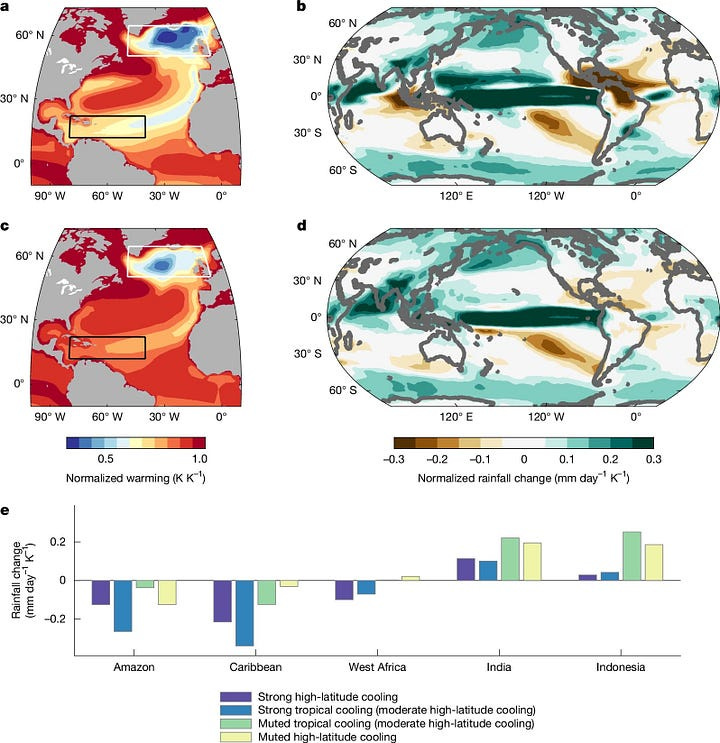

Dr DiNezio’s team identified which modern climate models best reproduced those ancient rainfall patterns. Then, they used those calibrated models to predict what might happen under future warming scenarios. The results were more alarming than expected.

Their simulations showed that as the AMOC weakens and the northern Atlantic cools, that cooling spreads into the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean. This change disrupts the delicate balance of moisture and heat that fuels tropical rainfall. Central America, the Amazon Basin, and much of West Africa, all regions that depend heavily on seasonal rain, would see drastic reductions in precipitation.

In some areas of the Amazon, annual rainfall could drop by as much as 40 percent.

That’s not just bad news for plants and animals. These ecosystems store vast amounts of carbon. The Amazon alone holds nearly two years’ worth of global carbon emissions. If droughts dry it out, and fires or dieback release that carbon into the atmosphere, it could speed up global warming even more. This is what scientists call a feedback loop: climate change disrupting ecosystems that, in turn, make climate change worse.

The idea of a tropical rainforest turning into a carbon source instead of a sink is no longer just hypothetical. I’ve seen firsthand how quickly forests can shift under stress. In my conservation work, I’ve helped design projects to protect biodiversity hotspots that rely on seasonal rain. One missed season can ruin harvests, spark wildfires, or force communities to migrate. These changes aren’t abstract; they’re deeply human.

What struck me most about this study isn’t just the scale of the potential droughts, but how little change it takes to set them in motion. Dr. DiNezio emphasized that even a modest weakening of the AMOC could increase the risk of tipping points in the tropics. That’s a stunning risk, especially given how interconnected our planet really is.

Still, the study isn’t a doom story. It’s a warning, and a useful one. We haven’t yet triggered a full collapse of the AMOC. But we’re inching closer. The authors are clear: the pace and magnitude of this slowdown depend on how quickly we reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We still have a window to act.

That’s why this research matters so much. It blends what we know from the past with what we can model about the future. It uses real data to reveal a world that might come sooner than we expect if we keep treating Earth’s systems like they’re unbreakable. They’re not.

Dr. DiNezio put it plainly: “We still have time, but we need to rapidly decarbonize the economy and make green technologies widely available to everyone in the world. The best way to get out of a hole is to stop digging.”

For those of us who’ve spent years reading the layers of mud and stone, that message couldn’t be clearer.

Thank you for supporting independent science writing! Your support helps keep these stories free for everyone, spreading science, trust, and action. I couldn’t do this without you!

If you enjoy my work and want to help me keep these stories free for everyone, I’d appreciate your support at any level that’s comfortable for you:

💡 $1/month or $10/year – A small boost with a big impact.

🌱 $2/month or $20/year – Supporting science communication.

🔬 $3/month or $30/year – Investing in evidence-based insights.

🌍 $4/month or $40/year – Expanding science for everyone.

🚀 $5/month or $50/year – Powering independent science writing.

Every contribution helps me continue creating content that makes science accessible, engaging, and impactful.

With Love,

Silvia P-M, PhD — Climate Ages

P.S.: Want to build a visible, fundable, and purpose-driven science brand?

Join the Outreach Lab waitlist and be the first to know when doors open this September.

What eats at me. It feels like we're all deer in the headlights. We're experiencing these changes. I'm experiencing the weather and watching the unprecedented fires. But I ask myself repeatedly 'What can I do to be part of what makes a difference?' ..and I doubt I'm alone.

Very interesting and well explained! Thanks for writing this.