Earth Is Our Only Data Point for Life in the Universe (For Now)

What fossils, planets, and probability can actually tell us about life beyond Earth

Studying fossils has made me increasingly curious about life elsewhere in the Universe.

As a paleontologist, I spend my time thinking about organisms that lived long before humans existed, long before forests, flowers, or even oxygen-rich air. I think about what it took for life to get started at all, and what it took for it to keep going through moments when the planet became hostile to almost everything alive.

Somewhere along the way, a simple question kept resurfacing. If life could begin and persist here under such changing conditions, what does that tell us about life on other planets?

Most people assume that discovering life elsewhere is mainly a technical problem. Build better instruments. Look farther. Analyze more planets.

I used to think that too. It feels reasonable. Earth is one planet among billions. Life exists here. With enough searching, it should turn up again.

Then the paleontologist in me pushes back.

So far, we only know of one planet that hosts life for certain. Not one kind of organism. One entire biosphere. Every fossil, every genome, every ecosystem we have ever studied comes from the same place. Once you fully absorb that, the problem changes shape. We are not comparing many worlds. We are trying to generalize from one.

The shared assumption is that Earth is typical. It seems sensible. Earth has liquid water, a steady supply of energy from the Sun, and despite repeated global catastrophes, life on Earth was never completely wiped out. Those conditions appear to have allowed life to emerge early and diversify. From that, it feels natural to conclude that similar planets should behave the same way.

But deep time has a way of complicating simple stories.

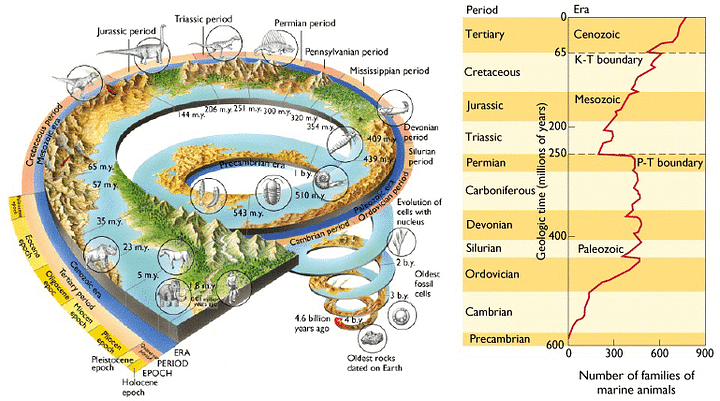

When we look at Earth’s early history, we see something puzzling. As far as we know, life appeared relatively early, within the planet’s first billion years. For a long time, this was taken as encouraging evidence. If life emerged “quickly” here, perhaps it does so easily wherever conditions allow it.

Scientists began to ask whether that conclusion was justified.

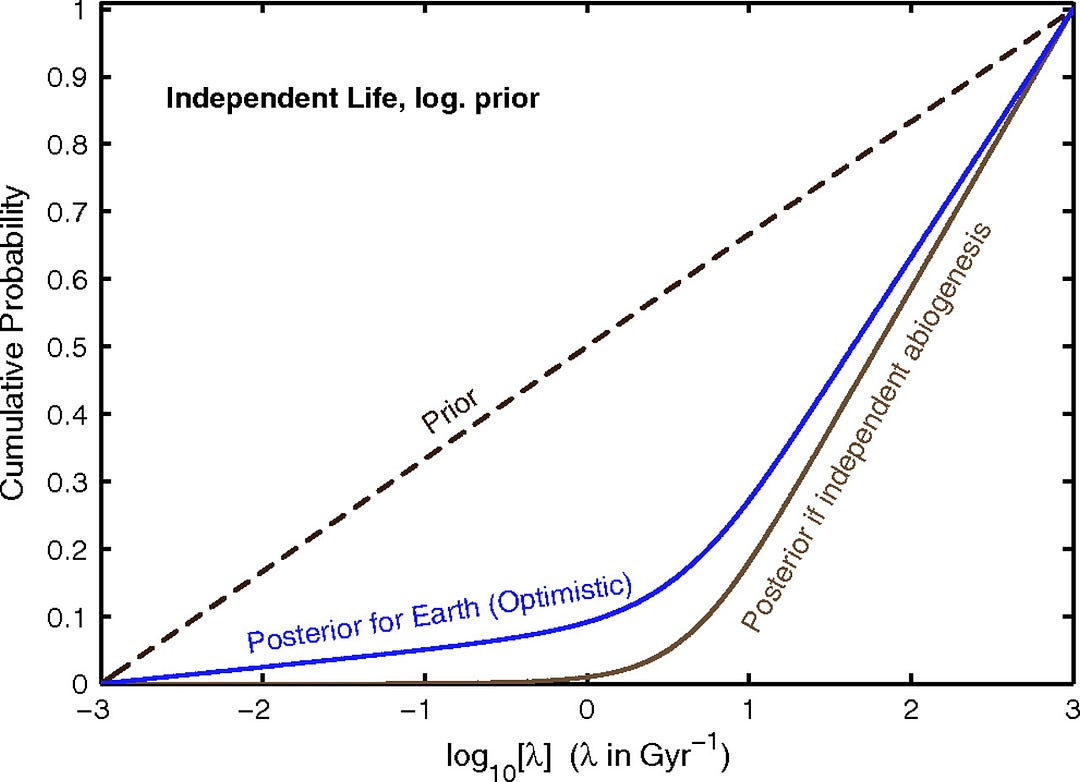

Instead of looking for more fossils or more planets, they examined the logic behind the claim using complex statistical methods. The key insight is uncomfortable but unavoidable. Because intelligent observers can only arise on planets where life began early enough to allow long evolutionary histories, the early appearance of life on Earth is an observationally biased data point rather than a representative sample.

In other words, one planet cannot define how common life is.

This creates a built-in bias. Earth had to succeed at least once. That means the early appearance of life is consistent with two very different realities. Life could be common in the universe. Or it could be extraordinarily rare, and Earth could be one of the few planets where all the right conditions happened to line up. The single data point we have cannot distinguish between those possibilities.

As a paleontologist, this feels familiar. One fossil can tell you what existed. It cannot tell you how common that organism was unless you have context (or another specimen). Without multiple sites, multiple layers, and multiple comparisons, frequency remains out of reach.

So where does that leave us?

It turns out Earth is still incredibly useful for astrobiology purposes, just not in the way people often imagine. Earth does not tell us how likely life is to arise. It tells us what life is capable of, once it exists.

The fossil record shows that life does not require stable or gentle conditions. For most of its history, Earth had no oxygen-rich atmosphere. Life persisted through global glaciations that may have covered the planet in ice, the famous “Snowball Earth Events”. It survived massive disruptions, from volcanic episodes to asteroid impacts. It even reshaped the planet itself, transforming the chemistry of the oceans and the air.

The Overlooked Piece of the Carbon Cycle That Froze the Planet

It’s a hot summer day, and you set your thermostat at 25°C (~78°F). Your air conditioner keeps things steady.

These are not abstract ideas. They are written in rocks, isotopes, and ancient sediments. From a deep-time perspective, Earth looks less like a fragile oasis and more like a system in constant negotiation with life.

This is where paleontology quietly informs astrobiology. Earth’s history acts as a long series of natural experiments. Each interval shows which physical and chemical conditions can support life over long periods and which ones push ecosystems toward collapse. It also shows that some signals we associate with life can appear without it.

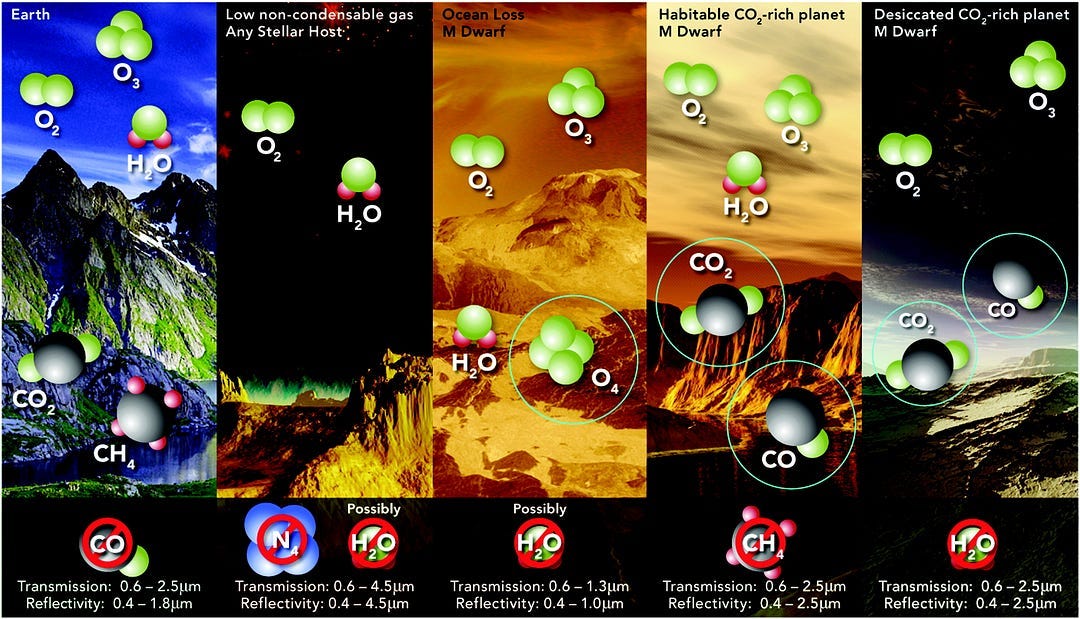

Oxygen is a good example. Today, oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere is tied to photosynthesis. But we know from planetary science that oxygen can also be produced by non-living processes under certain conditions. Without Earth’s history as a reference, it would be easy to misinterpret that signal.

Because of this, scientists are becoming more careful about what they look for on other planets. Instead of focusing only on planets that resemble modern Earth, many now search for more general patterns. They look for signs of a sustained chemical imbalance, where gases coexist that should not persist unless something is constantly replenishing them. They look for evidence that energy is being used and redistributed at a planetary scale.

This approach does not assume that alien life looks like us. It also does not assume that Earth is the standard all life must follow. It recognizes that life, whatever its chemistry, must interact with its environment in detectable ways.

From my perspective, this shift feels right. Paleontology has always been about context. Fossils mean little without the layers they come from. Life elsewhere will be the same. Signals only make sense when placed in planetary history.

Studying the origins and persistence of life on Earth does not give us answers about how many living worlds exist. It gives us a framework for asking better questions. What kinds of planets can remain active long enough for life to matter? What signs would require a continuous source of energy? How do we tell the difference between a living planet and one that only mimics life for a while?

Earth is not a blueprint. It is a reference case. Until we find a second example of life, it remains the only place where we can see the full arc, from origins to extinction and everything in between. For someone who studies life through deep time, that makes Earth not a limitation, but the most informative planet we could hope for.

Thank you for supporting independent science writing! Your support helps keep these stories free for everyone, spreading science, trust, and action. I couldn’t do this without you!

If you enjoy my work and want to help me keep these stories free for everyone, I’d appreciate your support at any level that’s comfortable for you:

💡 $1/month or $10/year – A small boost with a big impact.

🌱 $2/month or $20/year – Supporting science communication.

🔬 $3/month or $30/year – Investing in evidence-based insights.

🌍 $4/month or $40/year – Expanding science for everyone.

🚀 $5/month or $50/year – Powering independent science writing.

Every contribution helps me continue creating content that makes science accessible, engaging, and impactful.

With Love,

Silvia P-M, PhD — Climate Ages

The thing that really rankles me about the “finding Life on other planets” meme is the underlying hope that Life is possible on other worlds, making life on this one less unique. While if this planet, in its unique position and unique properties truly is the only one with Life, then we would be so ashamed of what we’ve done, using it essentially as a near-by resource planet to strip of materials to support our extraction-based economy, literally pushing Life out of our way at every turn.

How would this calculation change if we found microscopic organisms on a moon of Saturn, and we could demonstrate that they evolved separately from life on Earth?