Could Dinosaurs Raise Their Young at the Poles?

How fossils from the Arctic changed what we know about dinosaur reproduction

For much of the history of paleontology, dinosaurs have been imagined as animals that thrived where conditions were relatively forgiving. Not easy, but stable enough. Long growing seasons. Predictable plant growth. Winters that did not shut ecosystems down for months at a time. This picture shaped how scientists thought about dinosaur biology, from growth rates to feeding strategies to reproduction.

However, that framework began to strain once dinosaur fossils were found far from what we usually think of as dinosaur-friendly environments. High latitudes, both north and south, started yielding bones. These regions experienced extreme seasonality, including months of darkness each year. The question was not simply whether dinosaurs could pass through such places, but whether they could sustain a full life cycle there.

The most common solution for decades was migration. Large herbivores, the thinking went, could follow plant growth northward during the bright summer months and retreat south as winter approached. Carnivores could follow them. This idea fit comfortably with what was already known about dinosaur size, mobility, and ecology. It also avoided a deeper challenge to assumptions about dinosaur physiology.

But migration explains presence, not persistence. An animal can travel through a place without reproducing there. Raising young is different. It demands time, energy, and environmental stability during the most vulnerable stages of life. If conditions are too harsh, reproduction fails long before adults vanish from the fossil record.

That realization shifted the focus of research. Instead of asking whether dinosaurs lived in polar regions, we scientists began asking whether they reproduced there. And that question required a very specific kind of evidence.

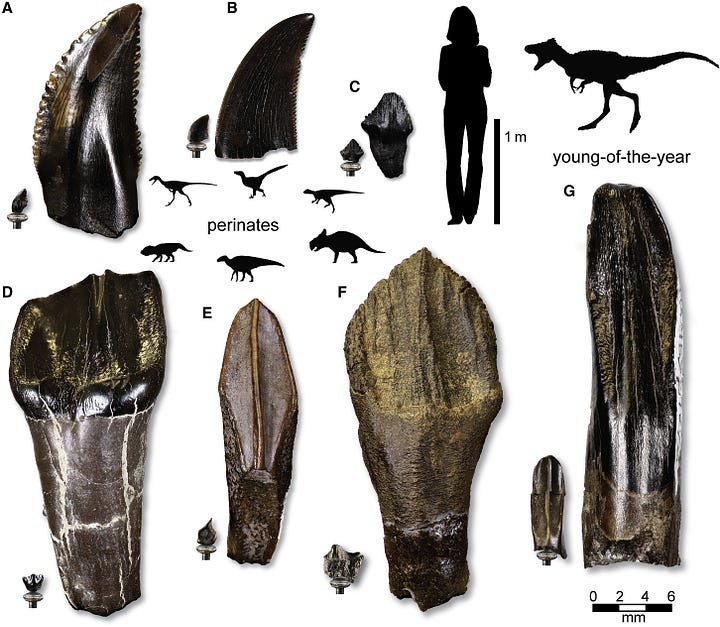

Adult bones are not enough. Even juveniles do not settle the issue. A young dinosaur could still have migrated after hatching elsewhere. To demonstrate local reproduction, paleontologists need traces of the earliest moments of life. Bones and teeth from animals that were only days or weeks old. Individuals who could not possibly have traveled long distances.

This is where the Arctic record becomes especially important.

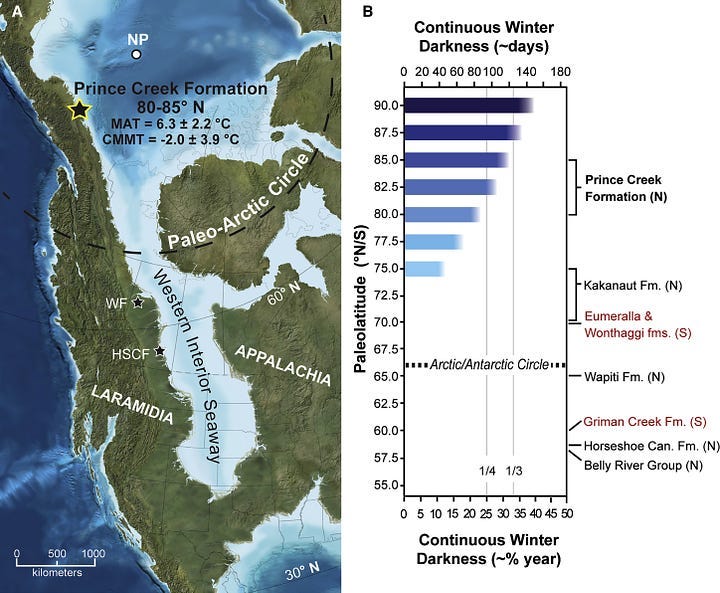

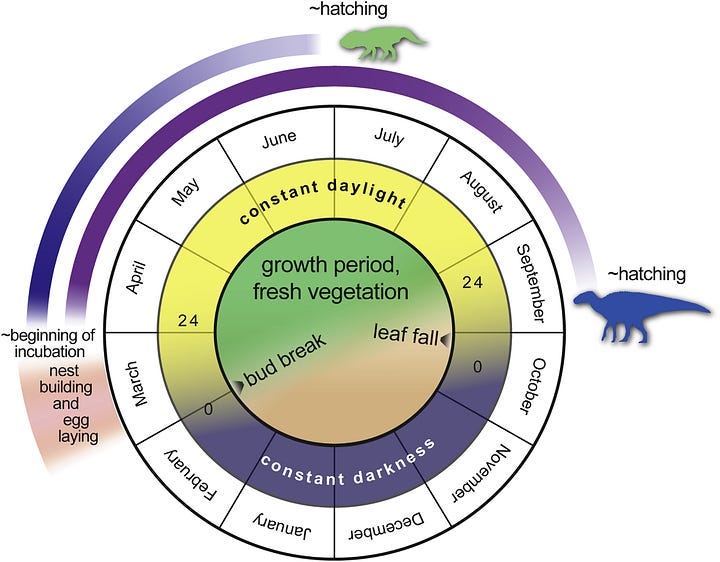

During the Late Cretaceous, parts of what is now northern Alaska sat at extremely high latitudes, well within the zone of prolonged winter darkness. These environments were not frozen year-round, but they were strongly seasonal. Summers were short. Winters were dark and cold. Plant growth was limited to part of the year, and food availability fluctuated sharply.

For a long time, dinosaur fossils from these regions were treated as curiosities. Interesting, but not necessarily transformative. They showed that dinosaurs could reach the Arctic. They did not show how dinosaurs lived there.

That gap began to close as researchers started paying attention to much smaller fossils. Tiny bones. Minute teeth. Fragments that could easily be missed without careful sampling and screening. These remains turned out to belong to newborn dinosaurs, animals that had died very shortly after hatching.

Their significance is hard to overstate.

Newborns cannot migrate. They cannot travel hundreds or thousands of kilometers. Their presence means that eggs were laid locally, incubated locally, and hatched locally. In other words, dinosaurs were not just visiting the Arctic. They were reproducing there.

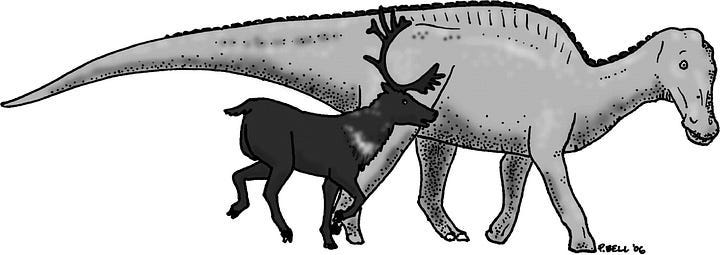

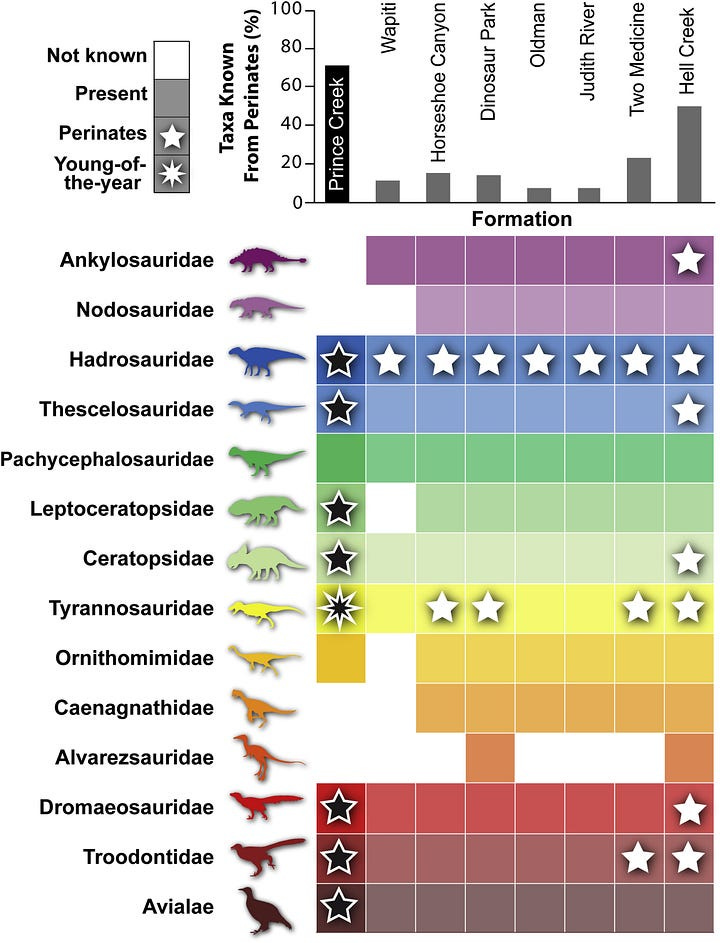

Even more striking is the diversity of species represented by these youngest remains. Both small-bodied and large-bodied dinosaurs are present. Plant-eaters and meat-eaters alike. This rules out the idea that only a few specialized species stayed behind while others migrated. The pattern points to entire communities living year-round at high latitudes.

Understanding why this matters requires stepping back to think about reproduction itself. Dinosaur eggs did not hatch quickly. Based on growth patterns preserved in embryonic teeth, incubation often took several months. Larger eggs took longer than smaller ones. In a highly seasonal environment, that timing matters.

In the Arctic, the window for successful reproduction was narrow. Eggs needed to be laid when temperatures were high enough for development. Hatchlings then had only a short period to grow before the onset of winter darkness. For large species, this meant entering winter at a very small size.

That reality places strong constraints on behavior and physiology. Long-distance migration becomes unrealistic when hatchlings cannot keep up. Producing multiple broods per year becomes unlikely when the growing season is short. Survival depends on enduring winter conditions rather than escaping them.

These constraints help explain why polar dinosaurs appear to have followed different life strategies than their lower-latitude relatives. Growth patterns preserved in bones suggest differences in development. Species found in the Arctic tend to be unique to those regions rather than shared with southern ecosystems. This points to long-term residency, not seasonal movement.

Climate plays a central role in this story, not as a background detail but as an active force shaping biology. Extended darkness limits photosynthesis. Short summers restrict plant growth. Cold winters increase energetic demands. Any animal living under these conditions must meet those challenges year after year.

The Arctic dinosaurs did so successfully for millions of years.

That success implies physiological traits that blur old boundaries. Insulation becomes important. Internal heat production becomes advantageous. Behavioral strategies such as reduced winter activity may have played a role, especially for smaller species. These are not speculative leaps, but careful inferences grounded in the limits imposed by the environment and the evidence preserved in fossils.

The broader lesson is not that dinosaurs were exceptional in a heroic sense. It is that life adapts to constraints in ways that are sometimes invisible until the right evidence appears. Fossils do not simply tell us who lived where. They reveal which strategies worked under specific conditions.

The Arctic was not a marginal edge of the dinosaur world. It was a place where climate demanded solutions, and evolution supplied them. Understanding that helps us see ancient ecosystems more clearly and reminds us that climate has always been a powerful force in shaping the possibilities of life.

The story is not about one paper or one discovery. It is about how asking a better question and looking more closely at the smallest pieces of evidence (quite literally) can change how an entire chapter of Earth’s history is understood.

Thank you for supporting independent science writing.

Climate Ages has officially become a Substack Bestseller, and it’s thanks to a community of 100+ paid subscribers who believe science writing should stay careful, clear, and accessible.

If you enjoy my work and want to help me keep these stories free for everyone, I’d appreciate your support at any level that feels comfortable:

💡 $1/month or $10/year – A small boost with a big impact.

🌱 $2/month or $20/year – Supporting science communication.

🔬 $3/month or $30/year – Investing in evidence-based insights.

🌍 $4/month or $40/year – Expanding science for everyone.

🚀 $5/month or $50/year – Powering independent science writing.

Every contribution helps me continue creating content that makes science accessible, engaging, and impactful.

With Love,

Silvia P-M, PhD — Climate Ages

Do we know if this was a proper thriving ecosystem with a variety of dinasaur species coexisting or an isolated species?

It makes me curious about their diet if access to plants would be so limited, but eating meat as an isolated grouping would require cannibalism... which I can't imagine would have been very successful.

It's interesting to imagine a full blown ecosystem filled with a wide variety of species not only surviving but thriving in such harsh landscapes...

I guess many of them could be aquatic dinos... very interesting! thank you for sparking my curiosity!

Very cool info! I always think of dinosaurs living in very hot, tropical climates. It's amazing to think they had such a more diverse ecosystem than what is normally thought of.