A Dying Ocean Current Is the Amazon’s Unexpected Ally (For Now)

New research reveals a surprising climate connection between the Atlantic Ocean and the Amazon rainforest, and why it won’t save us.

I spent a year working with a conservation nonprofit dedicated to the Amazon.

At first, I thought I was there to protect the rainforest, but slowly, I realized the forest was also teaching me how fragile everything is. It wasn’t just about saving a global carbon sink or preserving biodiversity hotspots.

The forest itself seemed alive in a way that made its vulnerability feel personal. There was a sense that if just one thing tipped too far, we could lose everything that keeps it alive.

So when I read about a recent study that uncovered a stabilizing link between the Amazon and the Atlantic Ocean’s currents, I paid attention. Not because I believed the forest had suddenly found a buffer, but because it reminded me how deeply entangled Earth’s systems really are and how little margin we have left.

The study, led by Dr. Annika Högner and published in Environmental Research Letters, shows that the weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) (yes, that deep-ocean current we usually hear about in the context of European winters or Hollywood collapse scenarios) has unexpectedly been helping the Southern Amazon.

As the AMOC slows, it cools part of the North Atlantic, subtly shifting wind and rain patterns. One result? A small but measurable increase in dry season rainfall over the Southern Amazon. That’s about 4.8% more for every 1 Sverdrup (Sv) of AMOC weakening. Since 1982, that effect may have offset about 17% of the forest’s rainfall loss.

It’s one of those stories that feels both surprising and inevitable. Of course, a distant ocean current would affect the rainforest. Of course, the forest would be caught in the crosshairs of systems far beyond its control. We just didn’t have the evidence until now.

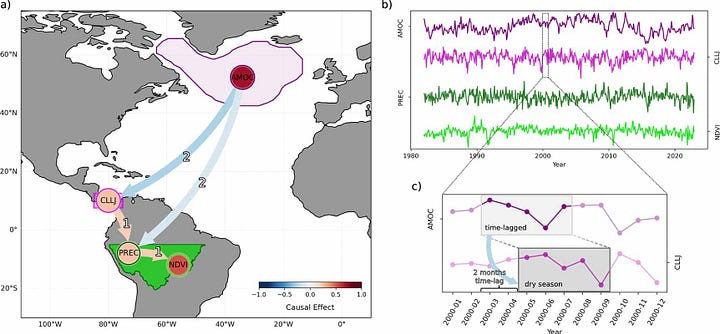

The researchers analyzed climate data spanning 40 years, applying a method called causal discovery, a powerful way of identifying not just correlation, but actual cause-and-effect relationships.

They focused on the dry season (May to September), when the rainforest is most vulnerable, and tracked how changes in the ocean, specifically surface temperatures in the North Atlantic, cascaded through atmospheric systems like the Caribbean Low-Level Jet before finally reaching the Amazon in the form of more rain. Not floods, not storms. Just slightly longer, slightly wetter dry seasons. And for a forest that can dry out and burn when rainfall drops even modestly, that makes a difference.

But it’s not enough.

The Amazon is still drying. Trees are still dying. Deforestation and rising temperatures are pushing the whole system toward a known, feared tipping point where the rainforest collapses into savanna. And no ocean current is strong enough to reverse that once it begins.

This is where the story intersects with a powerful piece written recently by my friend Ricky Lanusse, How Much Time Do We Have Before the Atlantic Ocean’s Collapse? It’s an essay that unpacks the current state of the AMOC with clarity and urgency, tracing how what began as a cinematic fear from The Day After Tomorrow has turned into a slow-moving but very real unraveling. His words stayed with me: “The timeline is up for debate. The direction is not.”

That’s what this new study reinforces. It doesn’t say we’re safe. It says we’ve bought time. And not even very much. It’s like watching someone cushion a fall with their arm. Yes, the landing hurts less, but the damage is still real, and the trajectory hasn’t changed.

Lanusse writes about the AMOC’s weakening not as a distant crisis but as something we’re already living through: in heatwaves, floods, and marine heat anomalies that defy categories. And that’s the part we need to remember: none of these tipping points exist in isolation.

The ocean isn’t “over there,” and the rainforest isn't “down there.” They are part of the same system, and right now, they’re both showing signs of stress. One may be offering temporary relief to the other, but it’s a bit like one passenger on a sinking ship bailing water for another.

You might delay the inevitable. But you won’t stop it if the hull’s still cracked.

Still, I see value in understanding this link, not just for science, but for hope. It means that even in a chaotic climate, not every interaction makes things worse.

Some systems push back. Some offer resilience… for a while. That’s not a reason to relax, but it is a reason to act more intelligently.

To protect forests not just because they store carbon, but because they respond to planetary shifts in real time. To cut emissions not just to “save the climate,” but to prevent the collapse of things we can’t rebuild.

The Amazon doesn’t need us to be its heroes. It needs us to stop breaking the things that help it breathe. And that includes faraway ocean currents, invisible airflows, and all the unseen links that tie our planet together.

What we do next matters. Because this isn’t about collapse in the abstract; it’s about living through what’s unraveling.

And it’s already started.

Thank you for supporting independent science writing! Your support helps keep these stories free for everyone, spreading science, trust, and action. I couldn’t do this without you!

If you enjoy my work and want to help me keep these stories free for everyone, I’d appreciate your support at any level that’s comfortable for you:

💡 $1/month or $10/year – A small boost with a big impact.

🌱 $2/month or $20/year – Supporting science communication.

🔬 $3/month or $30/year – Investing in evidence-based insights.

🌍 $4/month or $40/year – Expanding science for everyone.

🚀 $5/month or $50/year – Powering independent science writing.

Every contribution helps me continue creating content that makes science accessible, engaging, and impactful.

With Love,

Silvia P-M, PhD

Climate Ages

Jetzt alle weltweit miteinander füreinander mithelfen nicht später jetzt Bitte danke

“One result? A small but measurable increase in dry season rainfall over the Southern Amazon. That’s about 4.8% more for every 1 Sverdrup (Sv) of AMOC weakening.”

This is no big deal. The Gulf Stream barrels along at 160 Sv. There is a seasonal variation of 3 or 4 Sv, more in the summer, less in the winter.

When we take out vegetation and soils, replaced with hard impervious surfaces, stormwater increases even when annual rainfall amounts do not.

We see the Gulf Stream dissipating more energy by meandering further up onto the continental shelf. In 2007, the Gulf Stream surfaced in Svalbard and now their glaciers are melting.

More warm Atlantic water is going into the Arctic Sea. The ice melt can be seen happening not from the shore but from the Atlantic in a counterclockwise motion due to the Coriolis effect.

More Nutrient-rich cold Arctic water is jetting through the Denmark Straits where it meets warm, nutrient poor, less dense Atlantic water. Once it dove 11,000 feet to flow below. increasing in volume, it appears to now be closer to the surface cause a surface cold cell south of Greenland.

And the climate is changing. 80% is due to the largest greenhouse gas- water. 11% due to rising CO2.

Meanwhile property owners do not want to be mandated to let their lands hold the rainwater that falls on it. Instead municipalities pay the price and those living in the lowlands suffer. Sea levels rise.

Fires and clear cutting in the Amazon, the Congo, and Canadian forests are the greatest disruptors of the water cooling cycles warming the globe. Act locally to save us all.